Snake Island lies within the Nooramunga Marine and Coastal Park located in Corner Inlet, South Gippsland Victoria. The island is adjacent to Wilson Promontory National Park and at 35 square kilometre in area it is the largest sand island within a complex of barrier islands that protect the South Gippsland coast from the sometimes destructive weather and winds of Bass Strait.

For over 100 years local farmers have been grazing cattle on Snake Island. Cattle are driven to the island across the tidal shallows for both summer and winter agistment.

The Snake Island Cattlemens Association was formed to administer the agistment of cattle and in conjunction with Parks Victoria as the principle land manager, continue these traditional practises to ensure the sustainable management of the island for a multitude of diverse users.

The island being relatively remote is also popular with bushwalkers, kayakers, campers, recreational fishers and school groups who value the opportunity to experience the unspoilt and “get up close” natural environment the island has to offer.

A surprisingly large number of interrelated vegetation communities exist on Snake Island including woodland, scrubland, heath, freshwater swamps, mangroves and salt marshes.

These communities in turn support healthy populations of native Eastern Grey Kangaroo, Swamp Wallaby, Koala and Swamp Antechinus as well as the introduced Hog Deer.

Many bird species are also prevalent and large numbers of the increasingly threatened migratory waders roost along the coast after feeding on the inlets intertidal mudflats.

History of Snake Island

In 1909, the dairy farmers in the hill districts above Toora and Welshpool were granted access to winter agistment on Snake Island by the Victorian Lands Department.

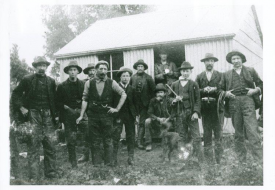

A bailiff was appointed to oversee the scheme and collect a fee from each farmer, while the farmers chose a ‘pilot’ who took responsibility for safely guiding the cows on the sea crossing to the island.

The use of the term ‘pilot’ was linked to the dangers of the crossing, where a sand-worm made all but a narrow path like quicksand for the cows. Such was their love of Snake Island and the respect felt by the farmers, these men in charge formed long partnerships.

Winter agistment on Snake Island, and at Yanakie, was an economic necessity for the hill farmers who were unable to provide fodder for herds of pregnant cows.In the early decades, each farmer who applied to send cows to Snake Island branded their cows by clipping a large number on the side of the animal.

The cows were walked down from the hill farms, often joining with others as they came along the roads to gather just east of Port Welshpool. Fortnightly crossings in autumn meant as many as 1200 dairy cows benefited from the sheltered bush and nourishing grasses on the Island.

Farmers had to participate in the crossing themselves, or send a son. For many young boys, turning sixteen was momentous because it meant they could go with the men to the Island.

The camps at the huts were legendary for the mix of stories, pranks by the youngsters and adventures. For most of the hill farmers, the trips to Snake Island were their only break from the isolation and hardship of farming.

The crossing was made at low tide, leaving at first light from the shores while the farmers, now called cattlemen, would ride along the flanks to keep the cows moving along the narrow track in the water.

At a point where the landmarks lined up, the herd would turn back towards Little Snake Island, where they walked to a crossing point on the Swashway. Once on Big Snake Island, the herd was walked for another few hours to the only permanent water on the Island before the cattlemen could return to the huts for a well-earned rest.

In the spring time, the muster and crossings were more dangerous, with strong winds and currents threatening the safety of the cows, now close to calving. Once back at Port Welshpool, the farmers worked together to draft out each man’s cows and they were walked back up the winding roads to the hills.

After 1960, modern technology and fertilizers meant there was less reliance on winter agistment. Over the next few decades, the Cattlemen’s Association took on a role as custodians of the traditions of Snake Island. The story of winter agistment is told in Snake Island and the Cattlemen of the Sea by Cheryl Glowrey